- Â

å September 2013

í REVISE RESEARCH AND CONTEMPLATE NEXT STEPS

We decided that next steps would be to clean up and revise the research to-date (you’ll find under Resources category), but feel our most pressing next task is to determine what we want to our outcome to be so we can be more clear what we’re looking for in the research and where we’re going. We should also plan the steps ahead. To that end, it seems it would be good to get conversation going.

I’m going to outlining a proposal below as a straw horse to be bent, added to, knocked-down, and reshaped. Please add your comments and ideas. Hopefully we have good conversation next class and can shape our plans for the rest of the semester.

Say our goal is POSSIBLE DIRECTIONS FOR GRADUATE GRAPHIC DESIGN EDUCATION.

We’d need to consider:

- What we imagine possible graphic design practices to be…

- by considering what characteristics of our context might impact what graphic designers do and/or what they make and how they make it (technology, culture, economics, etc.)

- As well as how we’d like see graphic design contributing

- (For example, Geoff Wardle, Director of Transportation Design (it used to be Automotive Design, but that no longer seemed relevant) at Art Center said of his new Program that while undergrads learn skills, tools and knowledge to design cars and present to their colleagues and community, “graduate students need to speak to the movers and shakers of the transportation world who are not designers — urban planners, architects, elected officials, and CEOs of car companies — by asking them ‘What bigger issues should we be addressing? How can we make transportation better in the future.'”)

PART 1

To be able to imagine possible practices and contributions, we’d need to do some research:

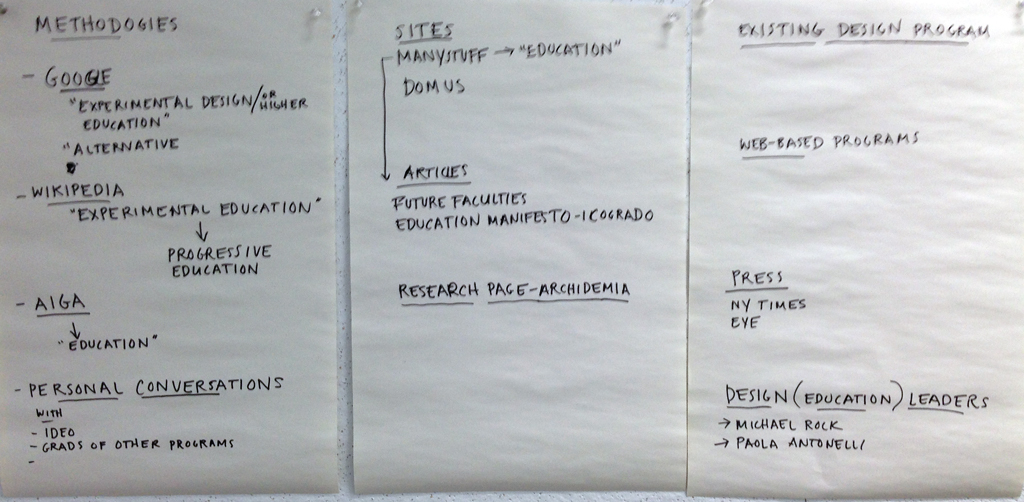

- Gain awareness of what the current dialogs are about graphic design education to see what others are imagining

- Gain awareness of experimental models of education taking place now as well as historically. We might want to categorize those models:

- New types of institutions (for creatives?)

- New types of programs (for creatives?)

- New types of classroom practices (for creatives?)

- Futurecasts

Then we’d assess what we learned from our research and determine what seemed interesting models/directions to pursue

PART 2

We’d then want to speculate:

- What are future practices that we imagine/would like to see/are needed?

- What are some possible configurations for the program that would education these future practitioners? What classes might be included; are there classes at all? Is there be a better/different way in which education might happen?; and where/how it might take place, etc.?

We might want to test/expand some ideas:

- Would we like to have conversations with others? Who might those people be? How might these conversations take place?

- Would we like to test some ideas? For example, we have a new model of teaching and want to try it out?

Create scenarios

- Ground our ideas, test them, and find a way to explain these through graphics or narratives

PART 3

Finally we’d want to assess what we accomplished and share it will others by publishing what we’ve learned

- Do we want to gather all we’ve researched done and learned into another form of delivery or simply share this site?

- Do we want to include our individual or collective theories?

- Do we want to visualize our models through charts and graphics or performances or some narrative form?

- Do we want to have an event to celebrate and share?

í RESEARCH: HISTORICAL EXPERIMENTAL EDUCATION

Our next step in to look at experiments in design education from the past. We’ve identified some programs and who’ll do the research as listed below.

On doing research: Wikipedia and internet are NOT reliable sources for research! Please use print resources unless the internet is the only resource. I recommend that you search through the CalArts library. There’s a search engine on the landing page. You can turn on “Search Worldwide” in drop down options. Select “Advanced Search” and add the databases, “Art Full Text” and “Art Index Retrospective.” Identify few sources that will give you the information below. Don’t get lost!

INCLUDE THE FOLLOWING INFORMATION:

- What is the program? (Title and bullet points of distinguishing characteristics)

- When was it?

- Why did it emerge? (What was it a reaction to? What motivated the founding?)

- What was the curriculum or model on which the program was based?

- A picture is always nice!

FORMAT/OUTPUT:

- Make sure type is big enough that we can quick identify information to compare one program with another.

- 8.5″ x 11″ pages (1 or 2 per program)

- Bring printouts to class AND e-mail to me!

PROGRAMS/RESEARCHER:

- Bauhaus – Sara

- Cranbrook 2-D and 3-D beginning with the McCoys – Sara

- Black Mountain – David

- Aspen Design Conference – David

- Bruno Munari (experiments and activities with children) – Calvin

- Ulm – Calvin

- Global Tools – Eline

- Norman Potter Construction School – Eline

- CalArts – Louise

í RESEARCH: CONTEMPORARY EXPERIMENTAL EDUCATION

- Name of an institution, program, practice, etc. (if it has one)

- Classification (a school, a program, a way of teaching, a way of learning, etc.)

- Very brief description of what distinguishes the model (a few words)

- Representative pic (if possible)

Please let me know that you got this post AND please toss out your ideas and comments regarding the “straw horse” I’ve laid out.

Hello! I am typing up some of my notes and responses to the outline tonight. What form of response does everyone think would be the easiest to access?

Thanks, Sarah! The idea is to have a conversation, so please put any thoughts you have in this thread. Thanks!

Just a reminder to post your thoughts about what our goal for the class might be. What is our goal? It should be something we’d like to know about graphic design education but that’s the only constraint. As a straw horse, I’d proposed our goals as “possible directions for graduate graphic design education” (and then offered a rough outline of what we’d likely need to do the rest of the semester in order to achieve that goal. Please pitch in your ideas about what you’d like to see us achieve!! It would be good to do this before class on Tuesday and preferably soon, so we can have toss ideas back and forth.

I am curious to first discuss what our personal goals as design students are. I think the more specific we can get when defining these prospects will help to highlight what experimental models are the most useful to examine.

Also, if we take a look at the trend of graphic design growing into other disciplines, how are we going to prepare ourselves to be able to communicate with people outside of our field? One of the things that I think would be hugely useful is the presence of language classes or clubs. I would also be curious to see how exposure to a new language could affect flexibility throughout the creative process.

It might also be helpful to consider what would be the absolute worst way to create a design program. What aspects of this model do we react violently to?

Finally, I would really like to see our findings organized in a written analysis because what we are trying to figure out is a broad subject and it might help to have it in a traditional format in addition to the website.

Let me know what you think. See you on Tuesday.

I JUST REALIZED THAT AN EXCELLENT THREAD IN THE CONVERSATION END UP WITH THE WRONG POSTING (THIS IS FLAW WITH THE THEME DESIGN.) I’M PASTING ELLIOT’S COMMENT BELOW FOLLOWED BY MY RESPONSE IN HOPES OF KEEPING THE CONVERSATION GOING UNDER THIS POSTING.

Although I’ve only been present for a portion of one of the classes thus far, I thought I’d quickly post some thoughts on the goals of this course (and design pedagogy in general), as per Louise’s request.

“Possible directions for graduate graphic design education” is a great start, but leaves something to be desired, IMO. I’d propose that a goal for the course could be, in fact, discovering real goals for graphic design education, as a whole.

Throughout my undergrad, there were two streams of focus. One was the vocational side of things: learning how to use CS, hard-and-fast rules about typography, how to bullshit, digital to analogue reproduction, and so forth. Second, there was an emphasis on developing a theoretical framework to situate one’s self in. Thus, I developed a strong framework based between Situationism and post-structuralism, and vast proficiencies in digital and print production. Though, due to the gaping chasm between these two aspects, this led to paralysis after graduating. I had learned how to apply design thinking TO the world, but not IN the world.

What really intrigues me is the opportunity to develop new design pedagogies which synthesize these two approaches. One way I think is effective in engaging both of these aspects is the use of “design fiction,” as demonstrated by Dunne & Raby, Noam Toran, etc. I see this is as an example of how we can learn/teach how to work IN the world, by extending our field beyond immaterial labour and the service-based paradigm we traditionally work within, in order to provoke change from an existing situation into a preferred one (which, I would argue, is a suitable definition of the practice of design). This approach also addresses issues of autonomy and collaboration with other disciplines.

I don’t know if this made any sense, but hopefully this contributes adequately to a critical discourse about the potentialities of design pedagogy. Any response to these musings would be appreciated.

___

Louise September 30, 2013 at 8:43 pm

Thanks for the comments, Elliot!

Re: Real goals for graphic design education. Hmmm… Are there? Or are there different configurations of goals depending on the values and of the various and diverse institutions (or entities in which design education takes place). (Also, if we’re looking goals, a distinction has to be made between undergrad and graduate ones.) Nonetheless I get that you’re asking a meta-question. Right on!

So maybe we could say that your proposal is that as a class we could define a goals graphic design education as we see is needed — and then “design” what that Program might look like.

Also, just a heads up that the work we’ve been doing the last few weeks is to look at different models experimental/alternative (graphic) design education — both contemporary models and well his historical ones. Seems like you probably have some ones to add. And, BTW, I’m going to present a recent project of Dunne & Raby’s in class tomorrow or the near future.

In going through this, I have a few ideas for direction though I’m not sure I’m as organized as Louise in my outline. But to keep the conversation going…

It seems that we’ve outlined the need to decide where the field is going—or at least where, as those who’ve decided to engage in the field at a graduate level, where we would like it to go. If I read it correctly, that seems to be in line with Louise’s Part 2. This begs certain questions that we’ve begun to answer informally, such as a leaning towards more interdisciplinary work. However, a further crop of questions then arises, namely, how do we actually encourage or teach to true interdisciplinary practices. But maybe I’m getting ahead of myself.

So in Part 2, we need to decide where the field is going in order to figure out what needs to be taught, and specifically, taught at the graduate level. I think this touches on a bit of the conversations we’ve been having between theory, making, and practical skills. I thought Elliot’s point about a gap between design thinking and practice to be an interesting and valid one, though perhaps that is just something that comes with time (?) From my perspective, the next link in this thought pattern is to figure out how can we contribute to what needs to be taught. What can I, as a practicing design, give to students to help prepare them for where the field is going? At the moment, if I had to teach a class, I’d probably reflect back on the teaching styles of my instructors. Might it be worthwhile to investigate if that is still the best method for instruction?

This ties back to some of the research we’ve already done. We looked at models of both current and historical forms of education but we’ve looked at them holistically. Perhaps next steps would be to tease apart these programs and see what specifically worked and how we might like to include them either in our teaching approach or an experimental program. If through discussion we can pin point what needs to be taught, how we can contribute and what experimental models we’d like to investigate further, I think then we’ll have a direction for Part 3 and we figure out what form these ideas should take.

Hope that makes sense and looking forward to hashing it out more tomorrow.

Any institutional education is a bit like practicing archery indoors, then stepping outside into the wind after graduating. Furthermore, it is hard for me to speculate directions for graduate design education while being within the very program I am speculating about, especially because I do not have an undergraduate degree in design (or a different grad degree) as a foil to my current situation.

That said, both Sarah and Elliot have good points so far. I think we need to establish some broad baselines of successful graduate design education, but this is also a difficult task because success is determined individually. Each person will have a different preferred outcome or specialization in mind within or about the field of graphic design (especially Peter Roy). Hopefully, they find the program which aligns best with their preferences, but most likely the path will not be linear. Perhaps we can find the intersection of what we deem lacking in most graduate graphic design educations with what we arrive as a group to be our own “preferred situations.”

I do think we need to speak with other design educators to escape our own insularity and just as another method of research gathering. I’m sure they each have a interesting perspectives and have been developing thoughts on this topic, as well as having a unique path that they took to become a design educator. As an outcome, I think it would be interesting to create a feedback loop through an event or publication or whatever form that allows people (perhaps these other educators) to respond and shape our own ideas.